16 Tissues and cells

On this page

The term tissue is used to describe a group of cells found together in the body. Microscopic observation reveals that the cells in a tissue can share morphological features and are arranged in an orderly pattern that achieves the tissue’s functions. From the evolutionary perspective, tissues appear in more complex organisms.

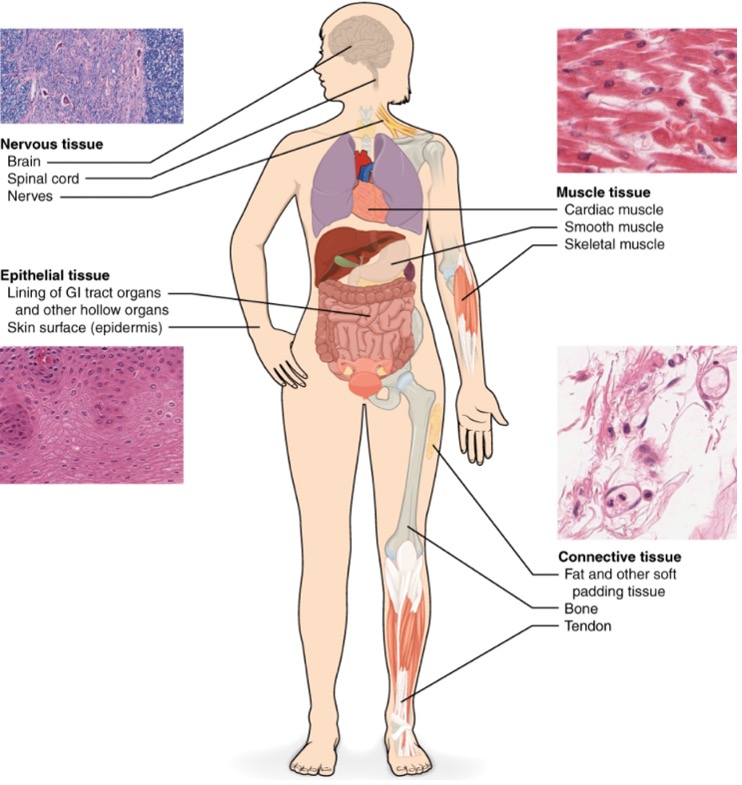

Although there are many types of cells in the human body, they are organised into four broad categories of tissues: epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous.

Each of these categories is characterised by specific functions that contribute to the overall health and maintenance of the body. A disruption of the structure is a sign of injury or disease. Such changes can be detected through histology, the microscopic study of tissue appearance, organisation, and function.

Case study

Case study

A 9-year-old female Labrador Retriever presents with lethargy, weight loss, and a distended abdomen. The owner reports that the dog has been drinking more water than usual and has a decreased appetite. Upon physical examination, the lab has pale mucous membranes, a distended abdomen, and mild jaundice. Palpation reveals an enlarged liver and spleen.

A full blood count reveals anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Biochemistry testing shows elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST), hyperbilirubinemia (increased bilirubin), and hypoalbuminemia (low albumin). Ultrasound imaging shows multiple nodules in the liver and spleen, suggestive of neoplastic lesions. Samples from the liver and spleen are obtained and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Sections are stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for microscopic examination.

Microscopic examination reveals cells forming irregular vascular channels filled with blood. The cells are pleomorphic (variable in shape and size) with hyperchromatic (dark) nuclei and frequent mitotic figures (dividing cells). These findings are consistent with a malignant tumour of vascular endothelial origin

Treatment involves a splenectomy (removal of the spleen) to prevent rupture and internal bleeding and partial removal of the liver to excise the tumour, a blood transfusion to address anaemia, intravenous fluids and nutritional support.

Understanding normal histology provides a reference point to identify pathological changes.

The four types of tissues

Epithelial tissue, also referred to as epithelium, refers to the sheets of cells that cover exterior surfaces of the body, lines internal cavities and passageways, and forms certain glands. Connective tissue, as its name implies, binds the cells and organs of the body together and functions in the protection, support, and integration of all parts of the body. Muscle tissue is excitable, responding to stimulation and contracting to provide movement, and occurs as three major types: skeletal (voluntary) muscle, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle in the heart. Nervous tissue is also excitable, allowing the propagation of electrochemical signals in the form of nerve impulses that communicate between different regions of the body (Figure 4.1).

Embryonic origin of tissues

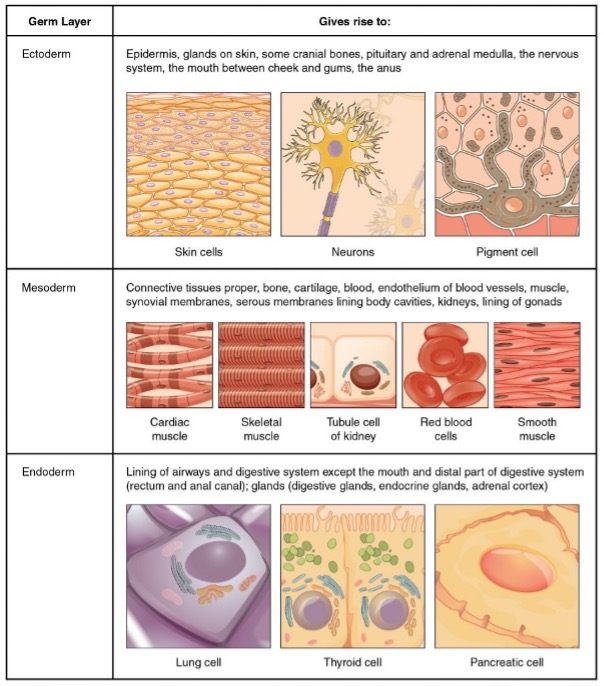

The zygote, or fertilised egg, is a single cell formed by the fusion of an egg and sperm. After fertilisation the zygote gives rise to rapid mitotic cycles, generating many cells to form the embryo. The first embryonic cells generated can differentiate into any type of cell in the body and, as such, are called totipotent, meaning each has the capacity to divide, differentiate, and develop into a new organism. As cell proliferation progresses, three major cell lineages are established within the embryo. Each of these lineages of embryonic cells forms the distinct germ layers from which all the tissues and organs of the human body eventually form. Each germ layer is identified by its relative position: ectoderm (ecto- = “outer”), mesoderm (meso- = “middle”), and endoderm (endo- = “inner”). Figure 4.2 shows the types of tissues and organs associated with the each of the three germ layers. Note that epithelial tissue originates in all three layers, whereas nervous tissue derives primarily from the ectoderm and muscle tissue from mesoderm.

Case study

Case study

A 2-week-old male Bulldog puppy is brought to the clinic with difficulty nursing, nasal discharge, and failure to thrive. The owner reports that the puppy frequently coughs and has milk coming out of its nose during feeding.

Upon physical examination, there is a visible gap in the roof of the puppy’s mouth, extending from the hard palate to the soft palate. This gap connects the oral and nasal cavities. Oral examination confirms the presence of a cleft palate, a congenital defect where the tissues forming the roof of the mouth do not fuse properly during embryonic development. Imaging may be performed to assess the extent of the defect and rule out other associated anomalies.

The patient is diagnosed with cleft palate, a congenital condition occurs due to incomplete fusion of the palatal shelves during embryogenesis. It can affect the hard palate, soft palate, or both, leading to an abnormal opening between the oral and nasal cavities.

Treatment involves palatoplasty (surgical repair of the cleft palate to close the gap) to restore normal function. This procedure is typically performed when the puppy is older and has gained sufficient weight to withstand anesthesia.

By understanding the intricacies of embryonic tissue development, veterinary students can better diagnose, treat, and prevent congenital anomalies.

Tissue membranes

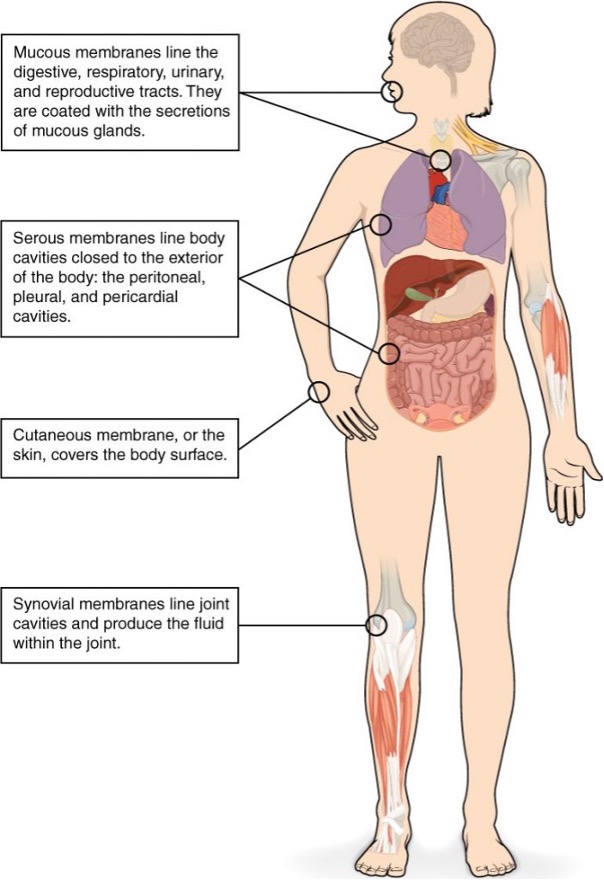

A tissue membrane is a thin layer or sheet of cells that covers the outside of the body (for example, skin), the organs (for example, pericardium), internal passageways that lead to the exterior of the body (for example, abdominal mesenteries), and the lining of the moveable joint cavities. There are two basic types of tissue membranes: connective tissue and epithelial membranes (Figure 4.3).

Connective tissue membranes

The connective tissue membrane is formed solely from connective tissue. These membranes encapsulate organs, such as the kidneys, and line our movable joints. A synovial membrane is a type of connective tissue membrane that lines the cavity of a freely movable joint. For example, synovial membranes surround the joints of the shoulder, elbow, and knee. Fibroblasts in the inner layer of the synovial membrane release hyaluronan into the joint cavity. The hyaluronan effectively traps available water to form the synovial fluid, a natural lubricant that enables the bones of a joint to move freely against one another without much friction. This synovial fluid readily exchanges water and nutrients with blood, as do all body fluids.

Epithelial membranes

The epithelial membrane is composed of epithelium attached to a layer of connective tissue, for example, your skin. The mucous membrane is also a composite of connective and epithelial tissues. Sometimes called mucosae, these epithelial membranes line the body cavities and hollow passageways that open to the external environment, and include the digestive, respiratory, excretory, and reproductive tracts. Mucous, produced by the epithelial exocrine glands, covers the epithelial layer. The underlying connective tissue, called the lamina propria (literally “own layer”), help support the fragile epithelial layer.

A serous membrane is an epithelial membrane composed of mesodermally derived epithelium called the mesothelium that is supported by connective tissue. These membranes line the coelomic cavities of the body, that is, those cavities that do not open to the outside, and they cover the organs located within those cavities. They are essentially membranous bags, with mesothelium lining the inside and connective tissue on the outside. Serous fluid secreted by the cells of the thin squamous mesothelium lubricates the membrane and reduces abrasion and friction between organs. Serous membranes are identified according locations. Three serous membranes line the thoracic cavity; the two pleura that cover the lungs and the pericardium that covers the heart. A fourth, the peritoneum, is the serous membrane in the abdominal cavity that covers abdominal organs and forms double sheets of mesenteries that suspend many of the digestive organs.

The skin is an epithelial membrane also called the cutaneous membrane. It is a stratified squamous epithelial membrane resting on top of connective tissue. The apical surface of this membrane is exposed to the external environment and is covered with dead, keratinised cells that help protect the body from desiccation and pathogens.