44 Microbial Growth and Symbioses

Provided with the right conditions (food, correct temperature, etc) microbes can grow very quickly. Depending on the situation, this could be a good thing for humans (yeast growing in wort to make beer) or a bad thing (bacteria growing in your throat causing strep throat). It’s important to have knowledge of their growth, so we can predict or control their growth under particular conditions.

While growth for muticelluar organisms is typically measured in terms of the increase in size of a single organism, microbial growth is measured by the increase in population, either by measuring the increase in cell number or the increase in overall mass.

Bacterial Division

Bacteria and archaea reproduce asexually only, while eukartyotic microbes can engage in either sexual or asexual reproduction. Bacteria and archaea most commonly engage in a process known as binary fission, where a single cell splits into two equally sized cells. Other, less common processes can include multiple fission, budding, and the production of spores.

The process begins with cell elongation, which requires careful enlargement of the cell membrane and the cell wall, in addition to an increase in cell volume. The cell starts to replicate its DNA, in preparation for having two copies of its chromosome, one for each newly formed cell. The protein FtsZ is essential for the formation of a septum, which initially manifests as a ring in the middle of the elongated cell. After the nucleoids are segregated to each end of the elongated cell, septum formation is completed, dividing the elongated cell into two equally sized daughter cells. The entire process or cell cycle can take as little as 20 minutes for an active culture of E. coli bacteria.

Growth Curve

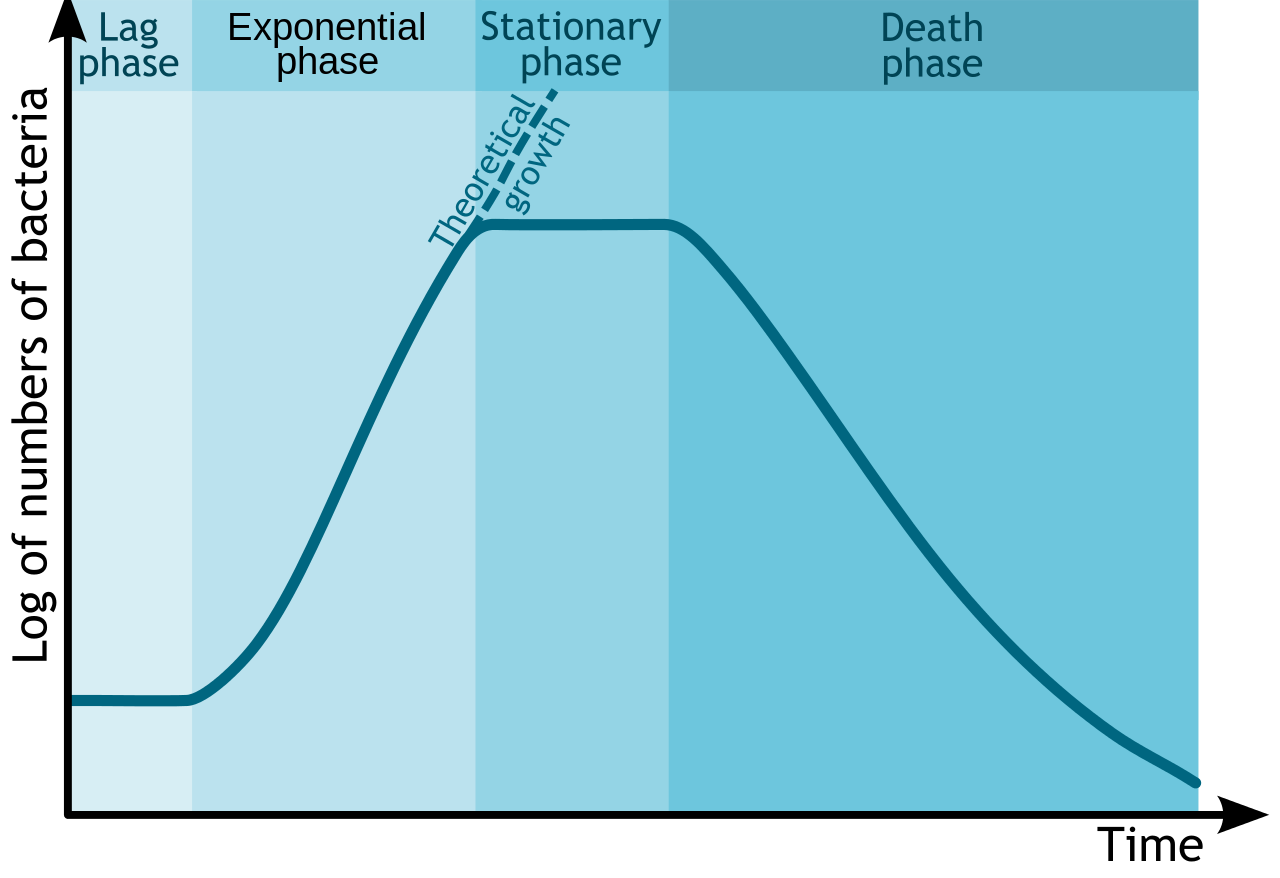

Since bacteria are easy to grow in the lab, their growth has been studied extensively. It has been determined that in a closed system or batch culture (no food added, no wastes removed) bacteria will grow in a predictable pattern, resulting in a growth curve composed of four distinct phases of growth: the lag phase, the exponential or log phase, the stationary phase, and the death or decline phase. Additionally, this growth curve can yield generation time for a particular organism – the amount of time it takes for the population to double.

The details associated with each growth curve (number of cells, length of each phase, rapidness of growth or death, overall amount of time) will vary from organism to organism or even with different conditions for the same organism. But the pattern of four distinct phases of growth will typically remain.

Lag phase

The lag phase is an adaptation period, where the bacteria are adjusting to their new conditions. The length of the lag phase can vary considerably, based on how different the conditions are from the conditions that the bacteria came from, as well as the condition of the bacterial cells themselves. Actively growing cells transferred from one type of media into the same type of media, with the same environmental conditions, will have the shortest lag period. Damaged cells will have a long lag period, since they must repair themselves before they can engage in reproduction.

Typically cells in the lag period are synthesizing RNA, enzymes, and essential metabolites that might be missing from their new environment (such as growth factors or macromolecules), as well as adjusting to environmental changes such as changes in temperature, pH, or oxygen availability. They can also be undertaking any necessary repair of injured cells.

Exponential or Log phase

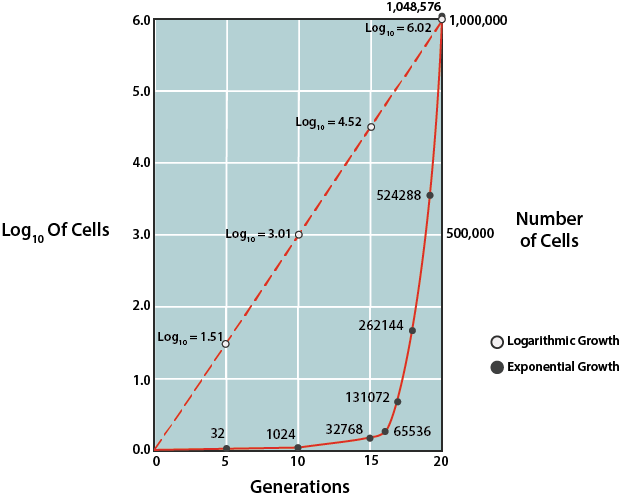

Once cells have accumulated all that they need for growth, they proceed into cell division. The exponential or log phase of growth is marked by predictable doublings of the population, where 1 cell become 2 cells, becomes 4, becomes 8 etc. Conditions that are optimal for the cells will result in very rapid growth (and a steeper slope on the growth curve), while less than ideal conditions will result in slower growth. Cells in the exponential phase of growth are the healthiest and most uniform, which explains why most experiments utilize cells from this phase.

Due to the predictability of growth in this phase, this phase can be used to mathematically calculate the time it takes for the bacterial population to double in number, known as the generation time (g). This information is used by microbiologists in basic research, as well as in industry. In order to determine generation time, the natural logarithm of cell number can be plotted against time (where the units can vary, depending upon speed of growth for the particular population), using a semilogarithmic graph to generate a line with a predictable slope.

Alternatively one can rely on the fixed relationship between the initial number of cells at the start of the exponential phase and the number of cells after some period of time, which can be expressed by:

where N is the final cell concentration, N0 is the initial cell concentration, and n is the number of generations that occurred between the specified period of time. Generation time (g) can be represented by t/n, with t being the specified period of time in minutes, hours, days, or months. Thus, if one knows the cell concentration at the start of the exponential phase of growth and the cell concentration after some period of time of exponential growth, the number of generations can be calculated. Then, using the amount of time that growth was allowed to proceed (t), one can calculate g.

Stationary Phase

All good things must come to an end (otherwise bacteria would equal the mass of the Earth in 7 days!). At some point the bacterial population runs out of an essential nutrient/chemical or its growth is inhibited by its own waste products (it is a closed container, remember?) or lack of physical space, causing the cells to enter into the stationary phase. At this point the number of new cells being produced is equal to the number of cells dying off or growth has entirely ceased, resulting in a flattening out of growth on the growth curve.

Physiologically the cells become quite different at this stage, as they try to adapt to their new starvation conditions. The few new cells that are produced are smaller in size, with bacilli becoming almost spherical in shape. Their plasma membrane becomes less fluid and permeable, with more hydrophobic molecules on the surface that promote cell adhesion and aggregation. The nucleoid condenses and the DNA becomes bound with DNA-binding proteins from starved cells (DPS), to protect the DNA from damage. The changes are designed to allow the cell to survive for a longer period of time in adverse conditions, while waiting for more optimal conditions (such as an infusion of nutrients) to occur. These same strategies are used by cells in oligotrophic or low-nutrient environments. It has been hypothesized that cells in the natural world (i.e. outside of the laboratory) typically exist for long periods of time in oligotrophic environments, with only sporadic infusions of nutrients that return them to exponential growth for very brief periods of time.

During the stationary phase cells are also prone to producing secondary metabolites, or metabolites produced after active growth, such as antibiotics. Cells that are capable of making an endospore will activate the necessary genes during this stage, in order to initiate the sporulation process.

Death or Decline phase

In the last phase of the growth curve, the death or decline phase, the number of viable cells decreases in a predictable (or exponential) fashion. The steepness of the slope corresponds to how fast cells are losing viability. It is thought that the culture conditions have deteriorated to a point where the cells are irreparably harmed, since cells collected from this phase fail to show growth when transferred to fresh medium. It is important to note that if the turbidity of a culture is being measured as a way to determine cell density, measurements might not decrease during this phase, since cells could still be intact.

It has been suggested that the cells thought to be dead might be revived under specific conditions, a condition described as viable but nonculturable (VBNC). This state might be of importance for pathogens, where they enter a state of very low metabolism and lack of cellular division, only to resume growth at a later time, when conditions improve.

It has also been shown that 100% cell death is unlikely, for any cell population, as the cells mutate to adapt to their environmental conditions, however harsh. Often there is a tailing effect observed, where a small population of the cells cannot be killed off. In addition, these cells might benefit from their death of their fellow cells, which provide nutrients to the environment as they lyse and release their cellular contents.

Environmental Factors

What do real estate agents always say? Location, location, location! It’s all about where you live, or at least adapting to where you live. At least it is for microbes.

Competition is fierce out in the microbial world (non-microbial world, too!) and resources can be scarce. For those microbes that are willing and able to adapt to what might be considered a harsh environment, it can certainly mean less competition.

So what environmental conditions can affect microbial growth? Temperature, oxygen, pH, water activity, pressure, radiation, lack of nutrients…these are the primary ones. We will cover more about metabolism (i.e. what type of food can they eat?) later, so let us focus now on the physical characteristics of the environment and the adaptations of microbes.

Osmolarity

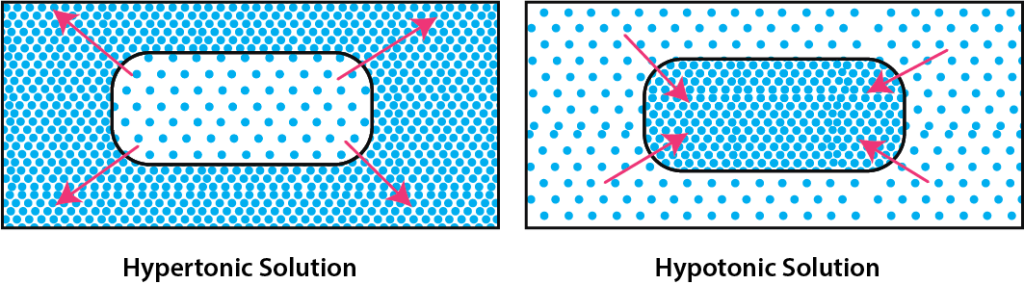

Cells are subject to changes in osmotic pressure, due to the fact that the plasma membrane is freely permeable to water (a process known as passive diffusion). Water will generally move in the direction necessary to try and equilibrate the cell’s solute concentration to the solute concentration of the surrounding environment. If the solute concentration of the environment is lower than the solute concentration found inside the cell, the environment is said to be hypotonic. In this situation water will pass into the cell, causing the cell to swell and increasing internal pressure. If the situation is not rectified then the cell will eventually burst from lysis of the plasma membrane. Conversely, if the solute concentration of the environment is higher than the solute concentration found inside the cell, the environment is said to be hypertonic. In this situation water will leave the cell, causing the cell to dehydrate. Extended periods of dehydration will cause permanent damage to the plasma membrane.

Cells in a hypotonic solution need to reduce the osmotic concentration of their cytoplasm. Sometimes cells can use inclusions to chemically change their solutes, reducing molarity. In a real pinch they can utilize what are known as mechanosensitive (MS) channels, located in their plasma membrane. MS channels open as the plasma membrane stretches due to the increased pressure, allowing solutes to leave the cell and thus lowering the osmotic pressure.

Cells in a hypertonic solution needing to increase the osmotic concentration of their cytoplasm can take up additional solutes from the environment. However, cells have to be careful about what solutes they take up, since some solutes can interfere with cellular function and metabolism. Cells need to take up compatible solutes, such as sugars or amino acids, which typically will not interfere with cellular processes.

There are some microbes that have evolved to extreme hypertonic environments, specifically high salt concentrations, to the point where they now require the presence of high levels of sodium chloride to grow. Halophiles, which require a NaCl concentration above 0.2 M, take in both potassium and chloride ions as a way to offset the effects of the hypertonic environment that they live in. Their evolution has been so complete that their cellular components (ribosomes, enzymes, transport proteins, cell wall, plasma membrane) now require the presence of high concentrations of both potassium and chloride to function.

pH

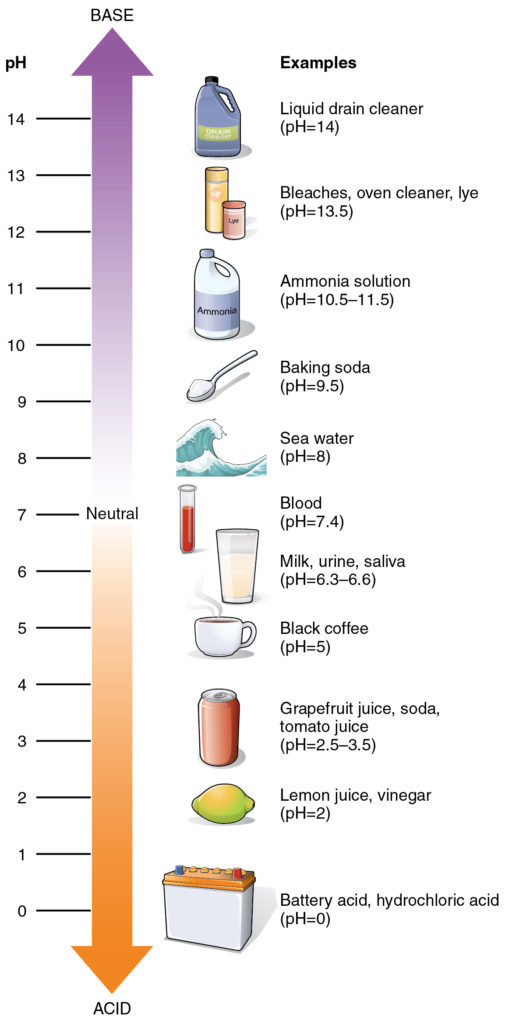

pH is defined as the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion concentration of a solution, expressed in molarity. The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14, with 0 representing an extremely acidic solution (1.0 M H+) and 14 representing an extremely alkaline solution (1.0 x 10-14 M H+). Each pH units represents a tenfold change in hydrogen ion concentration, meaning a solution with a pH of 3 is 10x more acidic than a solution with a pH of 4.

Typically cells would prefer a pH that is similar to their internal environment, with cytoplasm having a pH of 7.2. That means that most microbes are neutrophiles (“neutral lovers”), preferring a pH in the range of 5.5 to 8.0. There are some microbes, however, that have evolved to live in the extreme pH environments.

Acidophiles (“acid lovers”), preferring an environmental pH range of 0 to 5.5, must use a variety of mechanisms to maintain their internal pH in an acceptable range and preserve the stability of their plasma membrane. These organisms transport cations (such as potassium ions) into the cell, thus decreasing H+ movement into the cell. They also utilize proton pumps that actively pump H+ out.

Alkaliphiles (“alkaline lovers”), preferring an environmental pH range of 8.0 to 11.5, must pump protons in, in order to maintain the pH of their cytoplasm. They typically employ antiporters, which pump protons in and sodium ions out.

Temperature

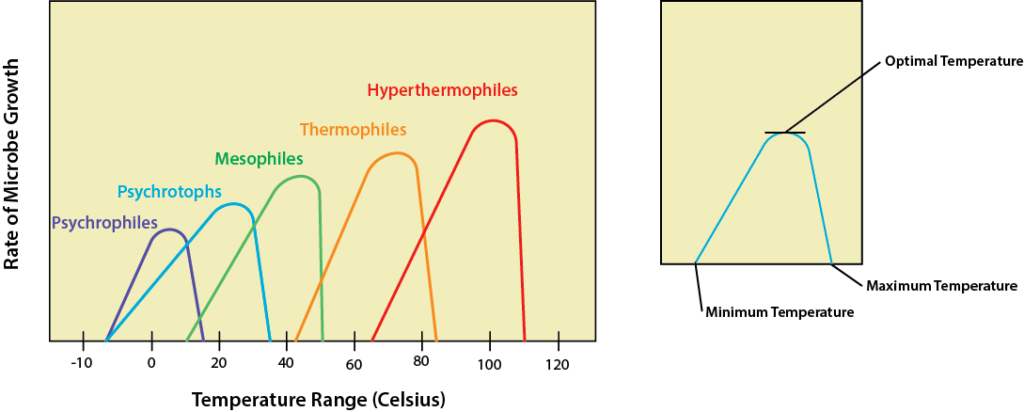

Microbes have no way to regulate their internal temperature so they must evolve adaptations for the environment they would like to live in. Changes in temperature have the biggest effect on enzymes and their activity, with an optimal temperature that leads to the fastest metabolism and resulting growth rate. Temperatures below optimal will lead to a decrease in enzyme activity and slower metabolism, while higher temperatures can actually denature proteins such as enzymes and carrier proteins, leading to cell death. As a result, microbes have a growth curve in relation to temperature with an optimal temperature at which growth rate peaks, as well as minimum and maximum temperatures where growth continues but is not as robust. For a bacterium the growth range is typically around 30 degrees.

The psychrophiles are the cold lovers, with an optimum of 15oC or lower and a growth range of -20oC to 20oC. Most of these microbes are found in the oceans, where the temperature is often 5oC or colder. They can also be found in the Arctic and the Antarctic, living in ice wherever they can find pockets of liquid water. Adaptation to the cold required evolution of specific proteins, particularly enzymes, that can still function in low temperatures. In addition, it also required modification to the plasma membrane to keep it semifluid. Psychrophiles have an increased amount of unsaturated and shorter-chain fatty acids. Lastly, psychrophiles produce cryoprotectants, special proteins or sugars that prevent the development of ice crystals that might damage the cell. Psychrotophs or cold tolerant microbes have a range of 0-35oC, with an optimum of 16oC or higher.

Humans are best acquainted with the mesophiles, microbes with a growth optima of 37oC and a range of 20-45oC. Almost all of the human microflora fall into this category, as well as almost all human pathogens. The mesophiles occupy the same environments that humans do, in terms of foods that we eat, surfaces that we touch, and water that we drink and swim in.

On the warmer end of the spectrum is where we find the thermophiles (“heat lovers”), the microbes that like high temperatures. Thermophiles typically have a range of 45-80oC, and a growth optimum of 60oC. There are also the hyperthermophiles, those microbes that like things extra spicy. These microbes have a growth optima of 88-106oC, a minimum of 65oC and a maximum of 120oC. Both the thermophiles and the hyperthermophiles require specialized heat-stable enzymes that are resistant to denaturation and unfolding, partly due to the presence of protective proteins known as chaperone proteins. The plasma membrane of these organisms contains more saturated fatty acids, with increased melting points.

Oxygen Concentration

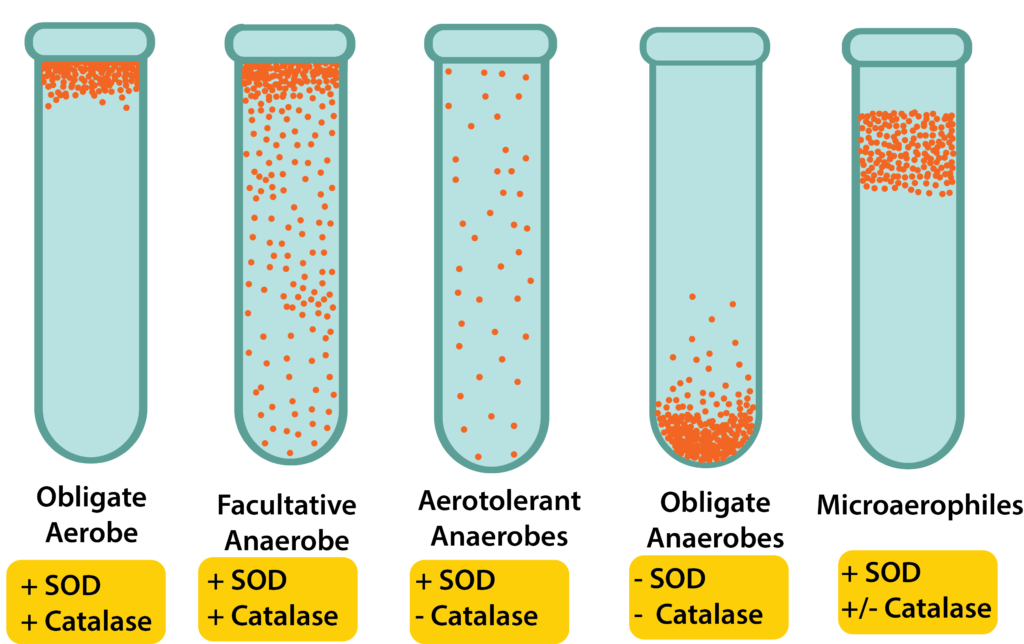

The oxygen requirement of an organism relates to the type of metabolism that it is using. Energy generation is tied to the movement of electrons through the electron transport chain (ETC), where the final electron acceptor can be oxygen or a non-oxygen molecule.

Organisms that use oxygen as the final electron acceptor are engaging in aerobic respiration for their metabolism. If they require the presence of atmospheric oxygen (20%) for their metabolism then they are referred to as obligate aerobes. Microaerophiles require oxygen, but at a lower level than normal atmospheric levels – they only grow at levels of 2-10%.

Organisms that can grow in the absence of oxygen are referred to as anaerobes, with several different categories existing. The facultative anaerobes are the most versatile, being able to grow in the presence or absence of oxygen by switching their metabolism to match their environment. They would prefer to grow in the presence of oxygen, however, since aerobic respiration generates the largest amount of energy and allows for faster growth. Aerotolerant anaerobes can also grow in the presence or absence of oxygen, exhibiting no preference. Obligate anaerobes can only grow in the absence of oxygen and find an oxygenated environment to be toxic.

While the use of oxygen is dictated by the organism’s metabolism, the ability to live in an oxygenated environment (regardless of whether it is used by the organism or not) is dictated by the presence/absence of several enzymes. Oxygen by-products (called reactive oxygen species or ROS) can be toxic to cells, even to the cells using aerobic respiration. Enzymes that can offer some protection from ROS include superoxide dismutase (SOD), which breaks down superoxide radicals, and catalase, which breaks down hydrogen peroxide. Obligate anaerobes lack both enzymes, leaving them little or no protection against ROS.

Pressure

The vast majority of microbes, living on land or water surface, are exposed to a pressure of approximately 1 atmosphere. But there are microbes that live on the bottom of the ocean, where the hydrostatic pressure can reach 600-1,000 atm. These microbes are the barophiles (“pressure lovers”), microbes that have adapted to prefer and even require the high pressures. These microbes have increased unsaturated fatty acids in their plasma membrane, as well as shortened fatty acid tails.

Radiation

All cells are susceptible to the damage cause by radiation, which adversely affects DNA with its short wavelength and high energy. Ionizing radiation, such as x-rays and gamma rays, causes mutations and destruction of the cell’s DNA. While bacterial endospores are extremely resistant to the harmful effects of ionizing radiation, vegetative cells were thought to be quite susceptible to its impact. That is, until the discovery of Deinococcus radiodurans, a bacterium capable of completely reassembling its DNA after exposure to massive doses of radiation.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation also causes damage to DNA, by attaching thymine bases that are next to one another on the DNA strand. These thymine dimers inhibit DNA replication and transcription. Microbes typically have DNA repair mechanisms that allow them to repair limited damage, such as the enzyme photolyase that splits apart thymine dimers.

Microbial Symbioses

Symbiosis, strictly defined, refers to an intimate relationship between two organisms. Although many people use the term to describe a relationship beneficial to both participants, the term itself is not that specific. The relationship could be good, bad, or neutral for either partner. A mutualistic relationship is one in which both partners benefit, while a commensalistic relationship benefits one partner but not the other. In a pathogenic relationship, one partner benefits at the expense of the other. This chapter looks at a few examples of symbiosis, where microbes are one of the partners.

The Human Microbiome

The human microbiome describes the genes associated with all the microbes that live in and on a human. All 10^14 of them! The microbes are mostly bacteria but can include archaea, fungi, and eukartyotic microbes The locations include skin, upper respiratory tract, stomach, intestines, and urogenital tracts. Colonization occurs soon after birth, as infants acquire microbes from people, surfaces and objects that they come in contact with.

Gut microbes and human metabolism

Most of the microbes associated with the human body are found in the gut, particularly about 1-4 hours after eating a meal when the microbial population dramatically increases. The gut microbiota is extremely diverse and it has been estimated that from 500-1000 species of bacteria live in the human gastrointestinal tract (typically described as from 5-8 pounds of bacteria!).

The gut microbes are essential for host digestion and nutrition, aiding in digestion by breaking down carbohydrates that humans could not break down on their own, by liberating short chain fatty acids from indigestible dietary fibers. In addition, they produce vitamins such as biotin and vitamin K.

Gut microbes and obesity

There has been increased interest in the microbial gut population, due to the possibility that it might play a role in obesity. Although currently hypothetical, research has shown that obese mice have a microbial gut community that differs from the microbes found in the gut of non-obese mice, with more Firmicutes bacteria and methanogenic Archaea. It has been suggested that these microbes are more efficient at absorbing nutrients.

Human microbiome and disease

It has been shown that microbiota changes are associated with diseased states or dysbiosis. Preliminary research has shown that the microbiota might be associated rheumatoid arthritis, colorectal cancer, diabetes, in addition to obesity.

Research

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) was an international research program based in the U.S. that was focused on the functions of gut microbiota. Some 200 researchers used advanced DNA-sequencing techniques to determine what microbes are present and in what populations.

Many current research projects are focused on determining the role of the human microbiome in both health and the diseased state. There is no doubt that our knowledge will continue to grow as we find out more about the vast populations of microbes that live in and on us.

Biofilms

Biofilms are a complex aggregation of cells that are encased within an excellular matrix and attached to a surface. Bioforms can form on just about any surface and are common in nature and industry, being found on the surfaces of rocks, caves, pipes, boat hulls, cooking vessels, and medical implants, just to name a few. They have also been around a long time, since the fossil record shows evidence for biofilms going back 3.4 billion years!

The microbial community of a biofilm can be composed of one or two species but more commonly contains many different species of bacteria, each influencing the others gene expression and growth.

Biofilm development

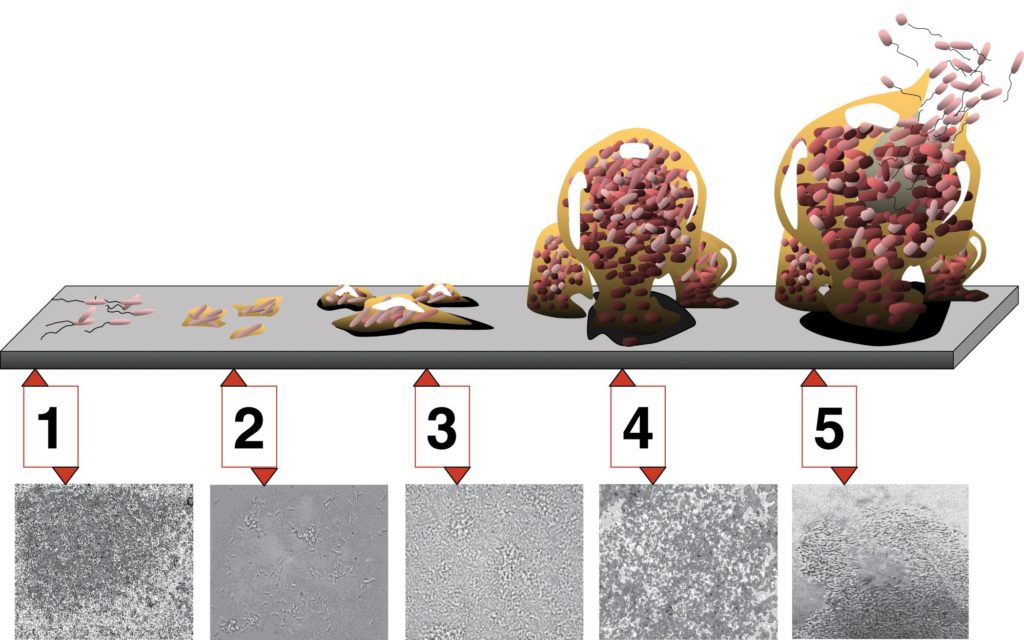

The basic steps for biofilm formation can be broken down into four steps:

- Cell disposition and attachment – in order for biofilm development to occur, free-floating or planktonic cells must collide with a suitable surface. Typically the surface has been preconditioned with the deposits of environmental proteins and other molecules.

- Colonization – cell-to-cell signaling occurs, leading to the expression of biofilm specific genes. These genes are associated with the communal production of extracellular polymeric substances. DNA released by some cells can be taken up by others, stimulating the expression of new genes.

- Maturation – the EPS matrix fully encases all the cells, as the biofilm continues to thicken and grow, forming a complex, dynamic community. Water channels form throughout the structure.

- Detachment and sloughing – individual cells or pieces of the biofilm are released to the environment, as a form of active dispersal. This release can be trigger by environmental factors, such as the concentration of nutrients or oxygen.

Biofilm Development. Each stage of development in the diagram is paired with a photomicrograph of a developing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. All photomicrographs are shown to same scale. By D. Davis [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

Cellular advantages of biofilms

Why do bioforms develop? There are certain advantages that cells enjoy while in a biofilm, over their planktonic growth. Perhaps most importantly, biofilms offer cells increased protection from harmful conditions or substances, such as UV light, physical agitation, antimicrobial agents, and phagocytosis. It has been shown that bacteria within a biofilm are up to a thousand times more resistant to antibiotics than free-floating cells!

A biofilm also allows a cell population to “put down roots,” so to speak, so that they can stay in close proximity to a nutrient-rich area. For example, a biofilm that develops on a conduit pipe at a dairy plant will have continual access to fresh food, which is much better than being swept away with the final product.

Lastly, biofilms allow for cells to grow in microbial populations, where they can easily benefit from cell-to-cell communication and genetic exchange.

Biofilm impacts

Biofilms have huge impacts throughout many different types of industry. Medical implants ranging from catheters to artificial joints are particularly susceptible to biofilm formation, leading to huge problems for the medical industry. Biofilms are responsible for many chronic infections, due to their increased resistance to antimicrobial compounds and antibiotics. A type of biofilm that affects almost everyone is the formation of dental plaque, which can lead to cavity formation.

Outside of medicine, biofilms affect just about any industry relying on pipes to convey water, food, oil, or other liquids, where their resistance makes its particularly difficult to completely eliminate the biofilm.

Quorum Sensing

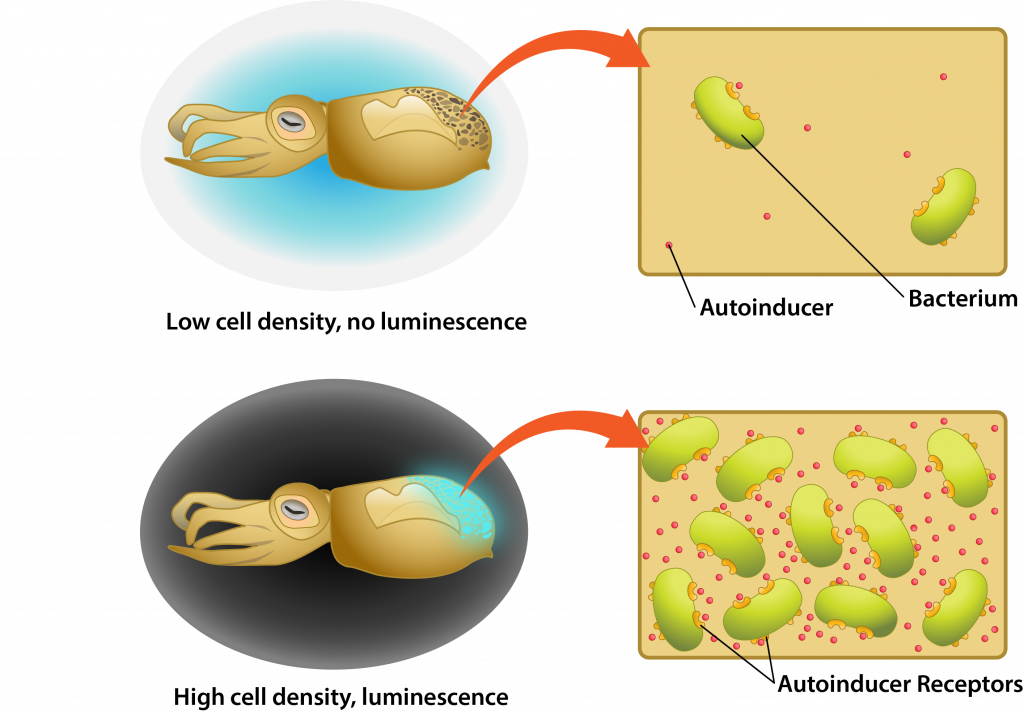

The word quorum refers to having a minimum number of members needed for an organization to conduct business, such as hold a vote. Quorum sensing refers to the ability of some bacteria to communicate in a density-dependent fashion, allowing them to delay the activation of specific genes until it is the most advantageous for the population.

Quorum sensing involves cell-to-cell communication, using small diffusible substances known as autoinducers. An autoinducer is produced by a cell, diffusing across the plasma membrane to be released into the environment. As the cell population increases in the environment the concentration of autoinducer increases as well, causing the molecule to bind to specific cellular receptors once a threshold concentration has been reached. The autoinducer then diffuses into the cell, often binding to a specific transcription factor. This produces a conformational change that allows the transcription factor to bind to the cell’s DNA, triggering expression of specific genes.

Quorum sensing example

One of the best studied examples of quorum sensing is the mutualistic relationship between the bioluminescent bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri and the bobtail squid. The bobtail squid actually has a light organ that evolved to house the bacterium, relying on its luminescence to provide a camouflage effect against predators. At low cell density the luminescence would not provide the desired effect, representing a waste in energy by the bacterial population. Therefore, quorum sensing is used so that the lux gene that codes for the luciferase enzyme necessary for luminescence is only activated when the bacterial population is at sufficient density.

Key Words

binary fission, multiple fission, budding, spores, cell cycle, closed system, batch culture, growth curve, lag phase, exponential or log phase, generation time (g), N, N0, n, t, stationary phase, DNA-binding proteins from starved cells (DPS), oligotrophic, secondary metabolites, death or decline phase, viable but nonculturable (VBNC).

osmotic pressure, passive diffusion, solute, hypotonic, hypertonic, mechanosensitive (MS) channel, compatible solute, halophile, pH, neutrophile, acidophile, alkaliphile, optimum temperature, minimum temperature, maximum temperature, psychrophile, psychrotroph, mesophile, thermophile, hyperthermophile, chaperone protein, electron transport chain (ETC), aerobic respiration, obligate aerobe, microaerophile, anaerobe, facultative anaerobe, aerotolerant anaerobe, obligate anaerobe, reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, barophile, ionizing radiation, Deinococcus radiodurans, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, thymine dimmers, photolyase.

symbiosis, mutualistic, commensalistic, pathogenic relationship, human microbiome, dysbiosis, Human Microbiome Project (HMP), biofilm, planktonic, extracellular polymeric substances/EPS, quorum sensing, autoinducer.

Study Questions

- How is growth measured in microbial populations?

- How do eukaryotes and bacteria/archaea differ in their reproductive methods?

- What are the steps of binary fission? What is happening at each step?

- Know what the growth curve of an organism grown in a closed system looks like. Know the various stages and what is occurring at each stage, physiologically. What can influence lag phase? What are the 2 differing explanations for cell loss in the death or senescence phase?

- Understand generation time and how can it be determined on a log number of cells vs. time graph. Know the advantage of plotting the log number of cells vs. time instead of the number of cells vs. time. What factors affect the generation time of an organism?

- Practice problem: Six Staphylococcus aureus are inoculated into a cream pie by the hands of a pastry chef. The generation time of S. aureus in cream pie at room temperature is 30 minutes. a) How many S. aureus are in the pie after 4 hours at RT? b) After 24 hours?

- What are all the descriptive terms used for microbes that live in different environments or the terms used for the environments that they live in? What does each term mean? In what types of environments are each microbial group found?

- What effect does solute concentration have on microbes? How can cells adapt when going from a low solute to a high solute environment and vice versa? What is a compatible solute? What microbial groups have a requirement for high solute concentrations? How do microbes differ in their response to water activity?

- How do microbes differ in their response to pH? What does pH affect in a cell and what do cells that live at high or low pH have to do to survive these conditions?

- How do microbes differ in their response to temperatures? What terms are used for these responses? If a cell is to grow at low or high temperatures, what adaptations does it need to make?

- How do microbes differ in their response to oxygen levels? Why would they differ? What enzymes are needed to adapt to environments containing differing amounts of oxygen?

- How do microbes respond to high pressure? To ionizing radiation? To UV light? What populations are resistant to these conditions?

- What is a symbiosis? What are different specific examples of symbioses?

- How is the human microbiome defined? What microbes does it include?

- What impact does or can the human microbiome have on its host?

- What are biofilms? Where do they form?

- What are the steps leading to biofilm formation?

- How do cells benefit from existing in a biofilm? What are the impacts of biofilms to humans?

- What is quorum sensing? How does the mechanism work?

- Describe the example of Aliivibrio fischeri and the bobtail squid. What role does quorum sensing play in the relationship between these two organisms?